Fantastic Points

We’ve been working on Fantastic off and on for a little over two years now, but its true history dates back much further. Like most things I do in my spare time, Fantastic is the result of a deep dissatisfaction with other options in the same space. At the core of Fantastic is its resource system, originally called “Fantastic Points.” We feel that this system solves a number of annoyances that have long been bugbears in our years playing RPGs. This is its origin story.

I’ve played a fair amount of Dungeons & Dragons (3rd, 3.5th, & 5th editions), but I’ve spent far more time complaining about it with my friends. One of the mechanics that I’ve given the most amount of gripe time to is the idea that a 20th level wizard – a being with power rivaling a god – can only cast Magic Missile four times before they can’t cast any first level spell at all. They can still cast Fireball (or even Wish!), but not Magic Missile. It’s always seemed wrong. Surely, such minor magic should be of no more concern to this wizard than throwing a stone.

Other classes in D&D suffer from the same problem. The text “Once per day, you may...” or similar shows up all the time in D&D and the genre at large, and each time it makes me a little sad. You end up tracking lonely little numbers with no interactions. Little segments of your character with no cohesion.

While endemic in 3rd edition, this is less of a problem in 5th edition. Spellcasters can cast lower level spells in higher level slots if they run out of the slots at the right level. The Paladin's smite evil mechanic is now powered by spell slots instead of being a flat, once per day ability as it is in 3rd edition.

Unfortunately, these changes are more patchwork than cohesive. You're still forced to track a collection of disparate resources across your character sheet. You still have to remember that these options are available to you.

When a character has a handful of abilities each with their own bespoke resource, it feels disjointed. These islands of mechanics may now be connected by occasional bridges, but that often just serves to highlight the islands without any connections.

Why can’t a bard sacrifice a spell slot to inspire his party members one more time? Why does his ability to cast spells improve over time, but not his capacity for inspiration? A druid can wild shape twice a day. If she does so, some core aspect of her "druidness" is fully depleted, but she is still able to cast her spells. Are these spells not also powered by the same magical well that lets her transform into animals? Perhaps not, but the rules offer no justification.

These separate, bespoke resources feel disjointed because they do not line up with our intuitive understanding of what it means to be exhausted. If you run a five kilometer race, at the end of it all aspects of your being have been spent, and you need a chance to rest. If somebody came up to you with a math quiz and challenged you to take it, you'd bat them away with tired frustration, because in that moment your mind is just as useless as your body. All of your "youness" has been poured into a single task. As humans, we understand this implicitly, and it feel strange that our roleplaying personas do not follow these same unwritten rules.

The Psionics books from the 3rd edition days got close to solving this problem, but they cultivated a second one. Psionic classes had a pool of psionic points they could use to invoke psionic powers. Each of these powers had a cost, and the cost grew the more powerful the power was. At first blush, this sounds great! Now you can use your power reserves as you see fit: lots of small powers, or a few large ones! Throw all of yourself at the problem!

The problem is, though, that in order to limit the higher tiered powers, they need to cost much more than the lower tiered powers. In order to support this cost expansion, you need to have a very large pool of points. This quickly becomes unwieldy, requiring lots of subtraction and paper and erasing to keep tally. It slows you down and the mechanic feels less satisfying as a result.

Bookkeeping is not fun. In fact, the smaller spells per day for the wizard are more fun because they are so clear. Small numbers are easy to reason about and easy to keep track of. It’s just that columns of small numbers that don’t interact with each other cohesively are a bummer.

This design problem has been simmering in the back of my mind for over a decade. As characters get stronger, I want the powers they could only use once to become the powers they can use as easily as breathing. I want new, more powerful powers to be more expensive, but I don't want the numbers to become large and unwieldy. I want to do this while keeping the numbers you have track to a minimum. Two years ago, that trusty back burner finally yielded something that I think solves these problems, and that is represented in the core resource mechanic of Fantastic.

The first bubbles formed while playing a Monk in 5th edition D&D. In D&D 5e, the monks use points called Ki to power their abilities. At the time, I was rebelling against the 5e character sheet, and I was keeping track of Thulwar Crystalfist the Deep Gnome Monk in a notebook. Monks only have a small number of Ki points, and a small number of abilities that use those points, so – on a lark – I wrote out Thulwar’s abilities on some blank cards I had on hand along with a small stack of “1 Ki Point” cards.

Playing Thulwar felt great. When I went to spend Ki, I would twist the appropriate number of cards sideways, pull out the card with all of the rules for the ability I was invoking, and slap it down on the table. Quick, direct, and playful.

Monks also benefit from 5e’s “Short Rest” feature, allowing their relatively small pool of Ki to be refreshed relatively frequently as opposed to just when the party camps for the night. That meant that my tapped Ki cards could be rotated straight and the whole process could start again.

Having Thulwar's essence written down on cards meant that I could easily shuffle through his abilities. All of the rules were right there on the card, so I didn't have to thumb through a book if I hadn't used an ability recently. His stack of Ki points were also easy to manage. No pencils, no erasing. Painless and immediate bookkeeping.

This amazing sense of tactility stuck in my mind, and I started wishing that I could play every kind of character in D&D like that.

The core of Fantastic’s resource system crystallized around this backbone. The first incarnation were “Fantastic Points”; cards that represented your ability to be fantastic at something. Rather than have each character archetype have a custom resource system, I wanted a common system for everybody. That way, you could learn one system and know the fundamentals of how to play any character. So, you might be “Physically Fantastic,” “Magically Fantastic,” “Acrobatically Fantastic,” and so on. What defined you would be the types of your resources, not necessarily how the resources behaved.

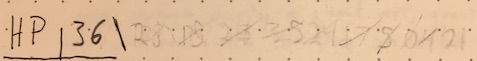

As the design of the game developed, the concept of “Fantastic Points” moved away from just representing what would be seen in D&D as a way to power class features and we started calling them “resource cards.” There are fives states a resource card can be in: Fresh, Pressed, Burned, Burned & Pressed, and Broken. The cards physically represent this by being, in order, face-up, rotated 90 degrees to the side, flipped over, flipped over & rotated 90 degrees, and discarded. Each step towards Broken represents depleting the resource.

Crucially, part of this system is how resources can recover. We wanted resources to recover more slowly the more they are depleted. Pressed resources can become unpressed (and thus rotated straight again) in the middle of combat through an action called Recoup. Burned resources can become Fresh again after resting for a time outside of combat or other stressful situations (a short rest). Finally, Broken resources come back slowly after a solid night of rest (a long rest). A single resource card represents a pool of power deeper than a single use, and the deeper you dip into that pool, the longer it takes for the pool to fully recover.

This leads to a host of interesting properties. Let’s start with one of the most obvious and impactful: ability cost. Ability cards – cool things your character can do – can draw upon your resources in two ways: Burst and Sustain. A card that costs “Burst 2 Vigor” to invoke means that you must either move one Vigor resource two steps towards Broken or move two Vigor resources one step. Sustain reserves a card to power an effect so that it cannot be used to Burst. This resource system establishes a power curve that is steeper than linear, and thus answers many of my decade-old complaints.

At first blush, you might think a character with 2 Vigor resources is twice as powerful than a character with 1 Vigor resources, but that is not the case. A character with 1 Vigor and an ability that costs Burst 2 Vigor can use that ability once every short rest or twice per day if they do not rest. However, if that character gains another Vigor card and is careful with how they manage those Vigor cards, they can use that ability unlimited times in a single combat encounter. Now, due to various limits on the Recoup action and the desirability of any given ability, the actual ceiling for this is functionally much lower. However, even without a chance to Recoup, the character with 2 Vigor cards can now call on that Burst 2 Vigor ability three times in a combat and still not be spent. Two Vigor cards is exponentially better than one.

This power expansion continues as you add more cards. A character with 5 resource cards is incredibly formidable, and can afford to Burst dozens of times in a single combat. This non-linear power curve means that – even at the height of power – the total number of resource cards a character will ever deal with can be counted on at most two hands. Similarly, the costs of abilities are kept clamped down. Unlike D&D Psions, characters in Fantastic don’t have to juggle 90+ Psy points and power costs of 12. The general range of costs in Fantastic is 1 to 3. Numbers are kept small and easy to consider.

The tactile nature of the resource cards makes a system that might appear complicated at first introduction actually be easy easily managed. In fact, flipping and twisting the cards creates fun and engaging gameplay. I’ve never felt that way about subtracting a number or crossing out a bubble.

In Fantastic, a character with few resources must be very careful with their starter abilities, while a character with many resources can toss around those same abilities all day without feeling strained. A power source that has natural exponential expansion means that players are not bogged down by dealing with exponentially expanding numbers.

Sustain costs create a critical wrinkle in this equation. Sustain represents focus or long term effort, such as hiking with a 60 pound backpack. Instead of demanding a resource be instantly depleted, Sustain instead reserves a resource or set of resources in order to invoke an effect. Physically, this is represented by moving the resource card behind the ability card it is sustaining.

Since a resource card sustaining an ability cannot be used to Burst or to Sustain another ability, this creates a natural tension. If you choose to sustain many cards, you constrain your ability to Burst. If you run out of Fresh resources, you have to choose what active sustain to drop. This leads to dynamic and engaging moments where strategies are forced to shift and sacrifices must be made. A character sustaining Armor Training, a card that lets them ignore armor penalties, is going to have a tough time deciding whether to Break their last non-sustaining resource or to drop Armor Training, take on the penalties, and hopefully be able to Recoup later and reactivate Armor Training's effects.

There are two other, smaller features of the system that are somewhat interesting. Fantastic's resources exist across two primary categories: Physical and Mental resource. Vitality and Vigor cards are Physical, while Will is Mental. A Physical cost can be filled by either Vitality or Vigor, but a Vigor cost must be filled by a Vigor card. The more specific a cost is (e.g. a Vigor cost is more specific than a Physical cost), the more expensive it is. Between this and untyped resources (e.g. Burst 1 Vitality / 1, where the second "1" can be fulfilled by any type of resource), the cost of a card can shift somewhat smoothly despite the disparity between requiring one Burst and two. This is one of the ways we tune an action's cost. Sometimes, all a card needs to sing is a small tweak.

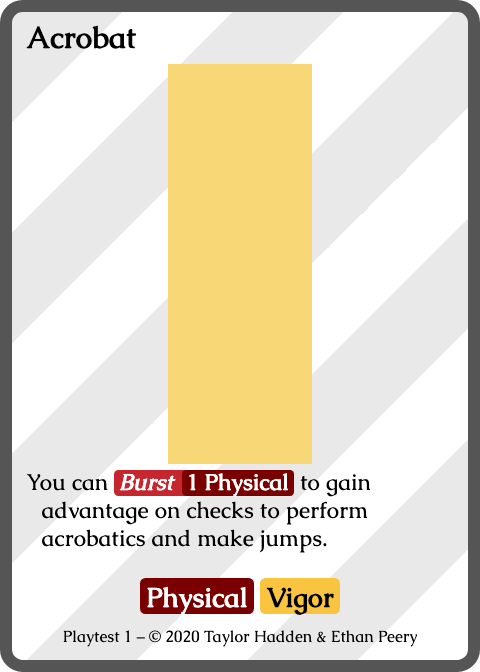

The last feature I want to highlight relates to how resource cards naturally flip over during play. Because of this intrinsic physical property, we can have other mechanics that change depending on how exhausted a character is without creating bloat. Take, for example, the card Acrobat.

As you can see, the rear, Burned side of Acrobat provides a weaker version of the effect on the Fresh front side of the card. In other systems, trying to keep track of an effect that changed depending on the status of a resource would be a pain. A feat in D&D that changed its effects depending on whether you were below half health or not would have more text to parse and is thus harder to understand. Worse, you’re less likely to remember that the rule has changed when you lose some health.

In Fantastic, these concepts are physically linked. The rules you see in front of you are the only ones that apply at any given time, so many conditions can be dropped and rules are easier to parse. Additionally, you are unlikely to forget the change of effect because you’re literally hiding one version of the effect and revealing the other as part of the core resource mechanism. This is an incredibly efficient way of handling a mechanical concept that can otherwise be a bookkeeping chore.

We have been very pleased with the success of Fantastic's resource system. We even used it as the way of tracking character health, but that's a story for another time. These mechanics and the simple act of playing with them conceal their real depth and engage you in a very simple, subtle way.